Art and artefacts that span human history contain many elaborate depictions of Gods, Deities and Icons. From the shining grandeur of Egyptian Kings and Queens, the wild and indulgent furies of the Greek Gods, to the romantic drama of Ophelia and the Pre-Raphaelites. Gods, deities and icons, whatever their form or function, have served as projections of society, encapsulating hopes, dreams, values and fears. Our continued hacking and immortalising of such pantheons, can been traced through art history and demonstrates a human narrative of recording information. The digital age may now have ushered in the likes of robots and artificial intelligence as the new pantheon, but it is important to remember that technology is no more immortal or divine as the sun, the moon or a blade of grass. While technological advancements have improved how data is recorded, it is still the responsibility of us, bone and blood, not metal and machine, to ensure we actively regulate and dictate how we share information in modern life. (McMullam, 2018).

The information that surrounds us, and that is represented in visual culture, now more accurately portrays the self, rather than that of an exalted pantheon. This is in part due to the readily accessibility of technology, which enables us to take a more central part in the digitisation and documentation of society. Our current addiction to upload, depict and deposit our lives on Instagram for example, may seem like a new fad, but there is something considerably deeper and older at work here. Throughout history there have been paintings, the writings of myths, legends and deeds, and mapping of towns, temples and distant stars, serving as documents of humanity. The world wide web and digital media are simply continuations of this dialogue. (Benjamin, 2008). We seem to never quite learn to just let things be or let things go, instead holding onto to our love letters, photographs, books and all the flotsam and jetsam that drifts into our lives. Given the chance, we will hoard the universe, its secrets and knowledge, above and beyond the Gods. It is therefore a testament to our sentimentality that we still value and vitally need libraries, galleries and museums to house, regulate and manage such collections of human knowledge.

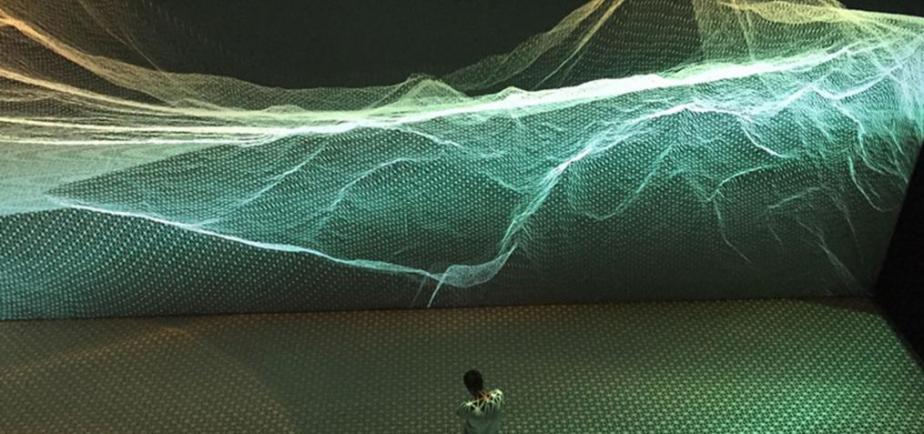

Alongside the start of the Digital Libraries module led by Lyn Robinson, I visited Central Saint Martins to see the exhibition ‘Metadata: How We Relate to Images’. This revealed a correspondingly complex world of images, hacking, digitality and immortality. The exhibition, set in cool, smooth concrete, put together a floating world of art and objects, focusing on the role of metadata in contemporary art and art history. A highlight was the work of Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, whose hack of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti is a great modern art heist, and a further example of the reproduction and immortality of ancient documents. The artists claimed to have scanned the Bust of Nefertiti, one of the masterpieces currently located in the Neues Museum, Berlin. They bravely made the resulting data publicly available, enabling anyone to use it for their own purpose. (Metadata: How we relate to images, 2018). While the heist raises many ethical questions around surrogate documents and authenticity, I could not help but marvel that the 3-D printed sculpture and digital prints on display, supposedly contained the exact data of an iconic piece of sculpture crafted thousands of years ago. Who would have thought that from sun blazoned Egypt, Nefertiti could be a tourist in the rain swept and slate skied city of London. The Bust of Nefertiti is also perfect example of the legacy of descriptive metadata. There is great power in standardising metadata and using text to describe the wordless. For non-textual items like paintings, artefacts and digital art, someone must create the metadata to tell us how to relate to and understand the documents meaning. Finding the words is another step in understanding and learning to see. (Gartner, 2016, p.41). A vase is simply a vase, but if metadata contextualises it and tells us it is a 400BC Greek Vase depicting Apollo, then the object suddenly has an ideology of history, appeal and value. It is in this, the careful nuance of accurate description, that the Gods live on and works of art have the potential to capture the imagination, entice spectators and impart the desire for further preservation and immortality.

The same impulse the Egyptians had to write information down, and create a visual language, is present today. 3000 years on and we are still scrawling words and images through the internet, which after all, is just a repurposing of scribes annotating on papyrus, acting as a sanctum where data and information can be shared and recorded. Now that the papyrus scrolls have moved into the archive and the machine moved into sight, there inhabits the perfect medium and incentive to digitise works of art, and practically everything else we can get our mortal hands on. Digital libraries having grown from the development of the web, are the next evolution in the lifecycle of the library and the provision of digital material. The idea of having one, singular repository of information is a lofty ideal, but there are the labyrinthine obstacles of interoperability of different digital formats and sustainability to contend with. (Bawden & Robinson, 2012, p. 154).

There is a common misconception that once a document has been digitised, like Al-Badri and Nelles have done so to Nefertiti, it can live immortally untarnished by the claws of entropy. Library and Information professionals must therefore work to standardise the construction and policies of preservation and metadata in digital libraries. The British Library are currently carrying out diligent work to set standards for metadata, so that both textual and non-textual documents continue to have a coherent structure, context and history. There are also digital ethics to consider, such as controlling and regulating linked data, distribution, stakeholders interests and open access. (Calhoun, 2014). Why should all this matter, I hear you ask? Knowledge! If we want to nurture future generations to exude knowledge as naturally as the sun gives out heat, then the information we leave behind has to be more sustainable, accessible, meaningful and truthful than just an echo, afterimage or footprint in the sand.

References:

Bawden, D. & Robinson, L. (2012) Introduction to information science. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

Benjamin, W. (2008) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. London, UK: Penguin Group.

Calhoun, K. (2014) Exploring digital libraries: foundations, practice, prospects. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

Gartner, R. (2016) Metadata: shaping knowledge from antiquity to the semantic web. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/city/detail.action?docID=4644424. (Accessed: 08th Feb 2018).

McMullam, T (2018). ‘The word of god: how a.i is defined in the age of secularism.’ Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/s/living-in-the-machine/the-word-of-god-how-ai-is-deified-in-the-age-of-secularism-5b24248f478e (Accessed: 03th Feb 2018).

Metadata: How We Relate to Images (2018)[Exhibition]. Lethaby Gallery, Central Saint Martens, London, UK. 10 Jan – 02 Feb 2018.

Images:

Bell, A. (2018). Digital Heist. [photomontage]. UK.